|

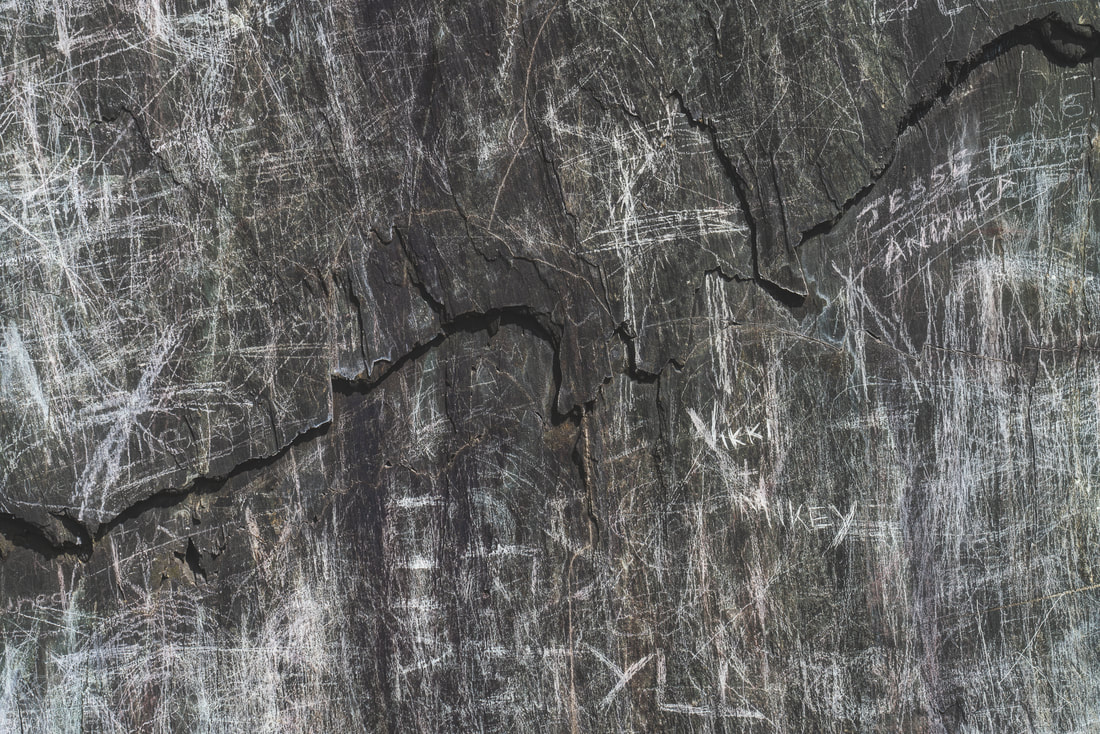

In early August this year I spent some time in North Wales, a magical area for landscape photography. The area contains some beautiful scenery that reminded me at times of the English lake district and at other times of the west coast of Scotland. As it was the height of summer my luggage contained both shorts and sunscreen, sensible and appropriate precautions, which turned out to be outrageously over-optimistic. On this trip, and indeed on every trip of 2019, I have been under a dark cloud (literally, not metaphorically) almost constantly. I have learned over time to embrace whatever atmospheric conditions I am given and tailor my photographic activities to the weather, there are things that work even better from a photography point of view in conditions which you could not describe as pleasant. When the rain pours down, as it surely did when I was in Llanberis, then the light conditions are often absolutely ideal for shooting waterfalls. The highly diffused light which results from a blanket of cloud is ideal for this kind of scene whereas strong direct light would create very harsh highlights and overly deep shadows. The incessant rain helps to swell the flow of running water and gives an extra vivid quality to the green foliage, especially when a polarising filter is also taken into use. The patterns that water makes while descending a steep rock face can often make for an attractive and slightly more abstract "intimate landscape". I sometimes notice people that seem to equate landscape photography exclusively with grand vistas and wide angle lenses. I do often shoot more expansive landscapes but I have found it helpful to employ many different focal lengths on my landscape photography trips, trying to be thoughtful about how best to capture the things that interest me in a scene. For instance, during this 10 day trip I employed 75 different focal lengths from 18mm to 400mm, a fairly typical statistic for me on such a trip. I have spent a lot of time in the UK this year (nearly 3 months in total), more than for any year since I moved to Finland 17 years ago, spending time in multiple areas of England, Scotland and Wales. I feel increasingly strongly that the remarkable past of these small islands is a defining factor in much of what is impressive, and also much of what is depressing, about modern Britain. The huge amount of surviving castles and strongholds which decorate the British countryside are reminders of very different times and a tribute to the people who have made the decisions needed to ensure that they are still (more or less) standing after many tens of generations. Before this trip I expected that the few days I had in Snowdonia would be my favourite part of the trip, the mountains in this area are not especially high (Wales has only 10 of the 350 highest peaks in the UK) but they are often quite steep and prominent compared to the surroundings which allows for some dramatic scenes. The relentless rain made me reconsider some of the (not very serious) climbs that I might otherwise have attempted, muddy and slippery conditions make quite a big impact on both the safety of a route and the effort needed to complete it... but luckily there was still much of interest a little closer to the ground. The various lakes in Snowdonia would have made for ideal photographic subjects in different conditions, but the high winds were killing all chances of reflections, just as they were for the entirety of my visit to the Lake District earlier in the year. One of my days in Snowdonia did at least offer interestingly mixed weather during the day, with clouds racing dramatically across the sky, something I later realised would have lent itself rather well to timelapse photography. Despite the generally grumpy weather the area was very well populated with hikers, tourists and the occasional other photographer, many car parks were full at locations across Snowdonia, but the vast open spaces seemed to manage to swallow the visiting hordes quite effectively and it was possible to find relative solitude by following the second or third most popular trail at a given location. The following day the downpour resumed and I found myself seeking out waterfalls once again. I travelled to my third "Fairy Glen" of the year ( after the famous one on the Isle of Skye and the not so famous one in Rosemarkie). At this location, I was completely alone and plucked up the courage to record footage for an instructional video with my thoughts about how to shoot such a scene... after recording multiple videos over the course of 45-60 minutes I realised that I really didn't much like the composition I had selected and was therefore making a "how to make make a bad picture" tutorial. Although that tutorial will likely never see the light of day I will try such things again in future in an attempt to get more comfortable on the other side of the camera as I think such content could be of use and interest at least to some of my photographer friends and maybe eventually to a wider audience. It is a challenge for a photographer to build an audience and I think that video content might be a way to expand my reach a little if it is done well. I continued to another waterfall nearby, the very touristy Swallow Falls, two miles west of Betws-y-Coed. As is often the case with tourist attraction locations such as this you are funneled (through a turnstile where they relieved you of a couple of pounds in this case) to a certain set of viewpoints and don't have a lot of choice about your shooting positions. Crowds of people also makes it a little harder to set up a tripod. Such places are often not ideal for landscape photography but if, like me, you also really enjoy seeing new places it is inevitable that you find yourself in such an environment now and then. In this situation I usually try to capture the classic shot you are directed towards (such as the one above) and then look for something which can be more my own. It is always possible to find something that has not been done millions of times before, but it is not always possible to find something which is any good. Looking at the scene above I thought that there would be a possibility to use a longer lens and capture a more intimate scene featuring just the overhanging branches on the far bank of the river and the cascading water of the falls. For anyone that finds themselves in this location, the Swallow Falls Hotel across the road from the waterfall entrance provides a cosy place to shelter from the elements and hearty pub meals to restore your energies. One common feature between this area and England's Lake District is the prevalence of slate mining as an activity. I took the opportunity to spend my final morning in Snowdonia visiting the site of the huge Dinorwic slate mine which is no longer active but at it's peak was the second largest slate mine in Wales and also in the entire world. This sprawling site has numerous paths running through it and affords views across the valley to the peaks on the other side as well as views long the valley itself. On this day the cloud cover percentage was reduced to only about 90% which is actually pretty ideal for daytime landscapes as there is the attractive possibility of the sun bursting through now and again and selectively illuminating the otherwise gloomy scene. This morning also happened to be the first day of the 2nd Ashes test between England and Australia so I was able to tune in, by phone or by car radio, to the familiar sounds of Test Match Special for eight hours a day for the following five days. The game of cricket, in all it's forms, but especially as a five day test match, lends itself like no other to the science and art of commentary, it is a sport which can be seen in vivid colour without needing to see any visuals. There are a number of reasons for this which are described below... for any heathens that do not already love cricket and are not prepared to be persuaded, I recommend skipping that part. Back to the slate mine, where some of my fellow humans have seen fit to leave their mark for others to see, the result is an image full of detail and texture. Well, I think that i will leave it there for this time, please join me next time as i continue to explore beautiful North Wales! Andy APPENDIX - Why cricket commentary is the highest form of the announcing arts The first key factor in elevating cricket commentary to the peak of the announcing arts is the perfectly detailed set of definitions. The vocabulary describing field positions is one aspect of this, it is truly wonderful how concisely the positions of the 15 persons on the field (bowler wicketkeeper, 9 other fielders, two umpires, two batsmen) can be described at any time, these definitions work equally well as a reference at all the different cricket grounds in the world and in all possible permutations. Similarly all the bowling styles, behaviours of the ball, batting strokes and outcomes of a ball bowled can be described with perfect clarity (to anyone who also knows the definitions) due to a beautifully complete, but versatile and flexible, set of definitions. This is already remarkable, but may not be absolutely unique among sports. The second ingredient which plays a key role in elevating cricket commentary to greatness is the element of time. Cricket takes ages! In a world where everything flashes past at ever increasing speed and attention spans are measured in fractions of seconds (how many of you looked at each one of my pictures in this post for more than a second each?)... a single game of test cricket has the audacity to last for five whole days. Seven or eight hours a day for five days! This is already quite something, but after all that effort there is still (historically) a 30+% chance that no result will be reached and the game will end in a draw. During these 40-odd hours of play (including breaks) the actual activity happens in short moments, a second or two of action about 90 times per hour, with frequent and extended periods where the drama, meaning and excitement (yes, excitement!) is to be found in the relentless overall trajectory of the play and the narratives that are woven around the teams and players rather then any particular ball bowled having an individual meaning. Cricket commentators might expect, in the best case, to spend noticeably less than 1% of the time explaining what is happening on the field and more than 99% of the time discussing other matters. Even these figures are over-optimistic, they assume that play will always be possible... but cricket is played ouside, often in England, and rain or wet conditions underfoot are fatal to the chances of play! It is quite possible for an 8 hour cricket commentary day to include not a single minute of actual cricket! The cricket commentary team must therefore collectively be a master of everything that might happen in the specific game itself, everything related to everything that might happen in the specific game itself, and also a host of other things, some of which may even be completely unrelated to cricket. They also have an unparalleled opportunity for exploration of a wide assortment of topics. The best of them, among which the BBC's test match special team can certainly be considered, manage to excel in this seemingly impossible task with ease and in style, keeping the listener interested from start to finish, again and again. The pinnacle of achievement among cricket commentary must surely have come last winter when the BBC did not manage to secure the rights to describe the actual cricket part of the cricket. So "the cricket social" was born. In this format the cricket commentators simply skipped the menial task of describing the (1-2 seconds ninety times per hour) of actual cricket and the result was masterful, 100% pure, commentary. Wonderful stuff. Recent posts

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAndy Fowlie See also:

SubscribeEnter your email address to receive notifications of new blog posts

Archives

December 2019

Categories

All

|

- Hub

-

Portfolio

- Flow 2019

- magical Vestrahorn 2019

- Fangorn 2019

- a snowstorm at Kintail 2019

- the village 2019

- a bolt from the blue 2019

- peaceful purple pastels 2019

- a Slovenian sunrise 2019

- the cormorant 2019

- Elgol on the rocks 2019

- weeds 2019

- pretty in pink 2019

- Ritsons Force 2019

- Sakrisoy on the Rocks 2019

- the Clappersgate eye 2019

- the Falls of Falloch 2019

- in the jaws 2019

- the devils teeth 2019

- tranquility 2019

- the old man of storr 2019

- Destinations unknown

- Articles

- Recognition

- Contact

- Store

- About

RSS Feed

RSS Feed